the legacy of The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall

corporate charter school chains, a censorship trial from the 1920s, and the complicated legacy of a touchstone in queer literature.

“Enfin, the whole world has grown very ugly, but no doubt to some people this represents pleasure” (Hall 382).

During an interview with a charter school I had applied to on a whim, the gentleman interviewing me stated that the school (which I will not name) taught the curriculum based on the merits of the Western Canon.

Flags colored red flew up in the back of my mind as I sat there in a house that wasn’t mine, a dog that wasn’t mine but was caring for perched on the couch facing the window that looks out on the street, and smiled placidly as the man droned on over Zoom and showed me a book on a curriculum from Barney Charter School Initiative of Hillsdale College and listed off names of every other Dead White Man in the Western Canon.

I put little to no effort into the rest of the interview from that point on. He kept on confirming all of my concerns that cropped up the moment we began talking: that I would have little autonomy in the classroom, that the bulk of the canon they would teach would be a list of men and the One (1) woman: Emily Dickinson.

Not a single other woman.

No people of color.

No international voices.

Everything that went against my own education in the Classics and my understanding of its importance.

Anne Carson and Emily Wilson would spit upon this curriculum.

I felt my blood broiling throughout the forty minutes I was interviewing and it just confirmed my growing distaste for the charter school model—a model I knew little about prior to applying to teaching positions— after other worrying interactions.

I feel especially insulted that Emily Dickinson is their token woman in their curriculum considering that there is mounting evidence that Emily Dickinson was not a straight, waif, ghost of a woman, but a passionate poet with great love and ardor for Sue Gilbert-Dickinson, to whom she has written the most beautiful poems and letters throughout the near four decades of their relationship and correspondence. Emily Dickinson’s work is brilliant, resonant no matter the time, and I have grown a better appreciation for her over the years as my taste has changed and developed, especially now that I’ve dipped into a further interest in poetry and begin crafting my own, knowing that such a woman loved another woman so deeply, so ardently, that she could still speak to me over almost two hundred years later.

I bet these assholes teach the dead-dry Fagles translation of the Odyssey instead of the brilliant one by Emily Wilson. Fuckers.

Socrates would look on with shame and disgust as he swallows the poison all over again.

Born in 2010, Barney Charter School Initiative is an outreach program based out of Hillsdale College. In their own words, they “[promote] a model of education that is rooted in the liberal arts and sciences, offers a firm grounding in civic virtue, and cultivates moral character.”

Hillsdale College, a small Christian college based out of Michigan, is also a hub of conservatism disguising itself as a liberal arts education.

It’s the antithesis of what it means to be within the realm of liberal arts, and their intent to is to completely gut the already strung out public school system.

The college has become a leading force in promoting a conservative and overtly Christian reading of American history and the U.S. Constitution. It opposes progressive education reforms in general and contemporary scholarship on inequality in particular. It has featured lectures describing the Jan. 6 insurrection as a hoax and Vladimir Putin as a ‘hero to populist conservatives around the world.’

I cannot emphasize enough how horrid this is, a fact that dawned on me after hearing all of these red flags in this one interview, which assured me that I would rather piss in the middle of a busy highway rather than work with such an institution that believes in book bans and whitewashing this ugly history of the country I live in, a fact we must contend with and reconcile, or at least attempt to.

They’re attempting to start up another 50 schools in the next few years.

If that doesn’t scare you enough, Former Vice President Mike Pence spoke at their graduation commencement in 2018.

One small mercy is that they got struck down from opening another school in Texas, though it’s only a mild comfort. After another job offer from a different charter school where there was a non-complete agreement in the offer letter (which I turned down, as the wording troubled me deeply), it’s only further alerted me to the concerning presence of charter schools—and how much like many universities and colleges now, they operate like corporate businesses rather than with a fulfilling education in mind.

For once, it makes me relieved and happy to have grown up in a relatively good public school system. Thanks for that one thing, Naperville.

Even if you put far more money and attention into your stupid football field rather than your crumbling foundations in the art wing of the original school while renovating back in 2008 to 2010. I see you.

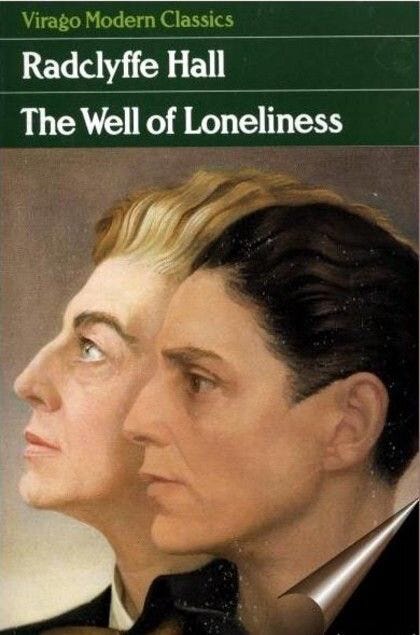

So. How does this all tie together with The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall?

Because this would be one of the first books banned and taken off of the curriculum, should such schools have even heard of it (considering how conservatives are beyond obsessed with the intimate lives of women, LGBTQ+ folk, and others, they definitely have), and there was an entire court case surrounding the book in 1928. Being an open lesbian in 1920s England was not illegal, per se, but it was seen as immoral and a critic, James Douglass of Sunday Express, explicitly called for its destruction:

In order to prevent contamination and corruption of English fiction, it is the duty of the critic to make it impossible for any other novelist to repeat this outrage. I saw deliberately that this novel is not fit to be sold by any bookseller or to be borrowed from any library.

Sure sounds similar to the book ban talks happening right now at the time of this writing.

The reason for its ban? Sexual explicitness and obscenity.

There is only one vague description of sex between two women: a single sentence. This is the sentence: “Stephen bent down and kissed Mary’s hands very humbly, for now she find could no words any more… and that night they were not divided” (313).

That’s it.

Really.

That’s all the sex that’s present in this novel. Jane Austen was more explicit in Sense and Sensibility and Mansfield Park. That should say enough. There’s passion, homoeroticism and agonized emotion, but there is little to no sex in this book. This is not at all a Sarah Waters style book.

One third novel, one third autofiction, and one third manifesto, The Well of Loneliness is the story of Stephen Gordon, a thoughtful, solemn lesbian and her struggles with her identity, her search for acceptance and tolerance and romantic entanglements. The novel goes through her life from before her birth, her childhood to her adolescence, and her adulthood. Her two love interests are Angela Crossby, a dissatisfied American housewife of a wealthy (and abusive) English landowner, and Mary Llewellyn, a younger woman she meets as an ambulance driver during World War One. Mary is the lover with whom Stephen has the most fulfilling relationship with. The novel also contains themes of spirituality, complicated mother-daughter relationships, the artistic process as a writer.

The book also functions as a manifesto pleading for acceptance and decrying the violent homophobia and intolerance of England in the 1920s, with a truly vivid and harrowing ending: from a more realistic prose turns surreal and spiritual as Legion from the Bible enters Stephen after she has lost the love of her life, Mary, to a man.

“‘We are coming, Stephen—we are still coming on, and our name is legion—you dare not disown us!’” (437).

And then, the final line of the book as Stephen’s despair over an unfair world swallows her,

“‘God,’ she gasped, ‘we believe; we have told You we believe… We have not denied You, then rise up and defend us. Acknowledge us, oh God, before the whole world. Give us also the right to our existence!’” (437).

And the book ends.

Setting the stage for the trend of tragic lesbian romances that would persist until Highsmith’s The Price of Salt, The Well of Loneliness is as much a manifesto and plea for tolerance and empathy as much as it is a tragic life story of an individual who cannot thrive in this narrow box of a world.

Many aspects of this book have not aged well. There is this gender essentialist idea with regards to homosexuality that’s woven into the novel after Hall discovered the writings of sexologists Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Havelock Ellis, and their ideas of homosexuality being a congenital sexual inversion.

While it asserts that being gay is an inborn trait that isn’t influenced by anything and is natural (true), it also borders on transphobic ideas of lesbians being ‘born with a man’s soul’ and Stephen is often described as such in the writing, by herself no less. Yuck.

There’s also aspects of classism: Stephen Gordon was born into a wealthy family and is independently wealthy throughout her entire life, even when she’s effectively disowned by her mother, Lady Anna, after her affair with a married woman is discovered. Mary is a common Welsh person born of modest means. The wealth disparity is not as addressed as it could be, and if Stephen had been born of lower means, chances are she would’ve never become a novelist in the story, nor would have Hall become a novelist either. While Hall wrote the novel with the intent to ask for tolerance for a deeply misunderstood people, her primary audience was a specific, elitist majority— “Stephen’s (and Hall’s) appeal appears to be centered only on acceptance by an upper-class, white audience: an appeal that was doomed to fail in part because of the earnestness of her petition” (Klein 620).

In addition to and a feature of this appeal to a very specific audience, there’s the single chapter of sheer racism where two Black men in Paris are described as having animal-like characteristics and are seen as more crude and sexual in a predatory manner (at least with one Black character).

Eugh.

Another interpretation of the book and Stephen Gordon as a character is also a relatively recent one that has solid grounds: that the story is one of a trans man being forced to present as a cis gender woman. Hall herself was called “John” by her loved ones and presented as what we might now call a butch lesbian, and Stephen herself often writes about how she’s unable to relate to her female peers at school when she’s young and how she finds more comfort in typically ‘male’ activities, mannerisms, and modes of behavior. This is not a detraction of the novel in any way, but another feature that adds a new layer of relativity to the book and why it might continue to resonate nearly one hundred years since its publication.

I am not trans nor non-binary, so I can’t speak on those grounds, although I would love to hear input from those who do interpret this book not as a lesbian story, but a transmasc one. For the sake of this article, I’m going to approach this book from the lens of it being a Lesbian Classic, because the novel itself has had a tremendous impact on lesbian pulp fiction. Stephen Gordon is regarded as the touchstone for the butch lesbian in novels and in media by which later work have lifted the imagery of, especially in the pulp fiction from the forties to the sixties in American literature. And there is a lot. Even later lesbian work have combated against the stereotypical butch lesbian image that Stephen Gordon popularized, which we’re still living through now.

Honestly, it’s nice to see a butch lesbian (should you read Stephen as such) be treated with such pathos instead of being the butt of a joke I’m so used to seeing.

I’m a lesbian, and although I don’t relate to everything with regards to Stephen’s journey and story, there is much about her story that I do. It’s clear to see just why this book continues to resonate now, contentious as its place is due to the sheer tragedy of the story.

Where this novel shines best is in the depiction of Stephen’s relationship to her mother, Lady Anna, her own sense of female masculinity, and the betrayal she feels when a man she considered a friend proclaims that he’s in love with her and wants to marry her.

The relationship between Lady Anna and Stephen is one that I especially empathize with, as I too have a difficult relationship with my mother and she has difficulty relating to me on many grounds, much of which has to do with my being gay and a creative. In the case of The Well of Loneliness, Lady Anne’s inability to relate to her daughter sews the seeds of resentment in her and she struggles to even say that she loves her child at all. Given the Edwardian and Victorian world that Lady Anna (a character heavily representative of Hall’s own mother, whom she had a poor relationship with) would’ve been raised in, she would have great difficulty in accepting and reconciling with Stephen’s tomboyish-cum-butch mannerisms and behaviors, which are such a contrast to the strict norms for women that she would’ve been raised in. Anna has expectations of what she expects out of a daughter and Stephen, including her name, is far more traditionally masculine than she’s comfortable with as it threatens her own sense of femininity—while her husband, Sir Phillip, who seems keenly aware of and tolerant and encouraging of his daughter’s lesbianness, raises her with love.

“‘I want Stephen to have the finest education that care and money can give her.’

But once again Anna began to protest. ‘What’s the good of it all for a girl?’ she argued. ‘Did you love me any less because I couldn’t do mathematics? Do you love me now because I count on my fingers?’” (54)

Little is given about Lady Anna’s background as a child, but the resentment and jealousy and a feeling of disconnect between daughter and mother bleeds through the text here. She’s been brought up in an environment that has strict ideas about what a woman out to be capable of and Anna takes (at least on the surface) pride and pleasure in being raised the way she was. However, Phillip and Stephen’s closeness is threatening to her because she’s lost a potential connection between herself and her daughter and Stephen doesn’t fit into the tightly fit box that Anna’s prepared for her.

Predictably, she lashes out.

She lashes out her own child, who cannot help the way she is. Stephen, who would be perfectly happy being who she is if not for her mother who hates her and dislikes the way she is.

My own sense of womanhood is somewhat complicated by the fact that I’m a lesbian and men are simply not in my mind’s eye when it comes to what I aspire to get out of a relationship. I’m not attracted to men. I have more androgen than what is typical of a cisgender woman due to a hormonal imbalance by way of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome, leading to facial hair and general hair growth that is unusual for cis women, the inability to lose weight easily, I have more muscle mass, my cycle is especially painful, and my fertility is skewed (although I have no plans of ever having children). I’m relatively muscular and buff with thick calves.

My mother pulled me out of swim lessons when I was ten years old. I was good enough that my instructor wanted to put me with the advanced middle school kids and I had a thought of joining the swim team in high school.

My mother’s reasoning for pulling me out of swim lessons was that she was afraid that the fat in my legs would turn to muscle and wouldn’t go away. That I would never lose that fat.

Everyone else is more obsessed with my body than I ever could be.

The way that Anna and Stephen’s tense relationship deteriorates after Phillip’s death resonates all too closely to an all-too common experience with other lesbians I’ve met, become friends with: the topic of the mother.

I don’t know if I would call myself a tomboy as a kid. Stephen certainly is in the novel. If I were to read her as a lesbian and not a trans man, I’d call her a butch lesbian or possibly a non-binary lesbian. I’ve been wondering about my own sense of gender for the past few years and I see much of myself in Stephen (minus the inordinate wealth). I liked things that were ‘traditionally feminine’ such as playing with Barbie dolls (although I abused those poor things horribly with melodramatic stories that would put that soaps I see playing on the TV at the gym to shame) but I’ve always felt more comfortable in pants, slacks, and slightly loose, button down shirts than skirts or dresses. I enjoy working out, hikes, swimming and a bougie craft beer. Does that make me a tomboy? Butch? I don’t know. Probably not. I haven’t worn a bra in over two years. Stephen would probably get on my nerves some for being a trust fund baby, but I could see myself cracking open a beer with her.

We would spend hours discussing our issues with our mothers.

Stephen describes the love for her mother as something that was thrust upon her by her father, not an integral part of her being (86). Whether or not Hall intends this to be the case, it’s bullshit based on how devastated Stephen is when her mother, having discovered her affair with another woman, disowns her and all but states she’s always disliked Stephen. When the affair falls apart, Stephen describes an unusual impulse:

“the impulse to confide in this woman within whose most gracious and perfect body had lain and quickened. She wanted to speak to that motherhood, to implore, nay, compel its understanding. To say: ‘Mother, I need you. I’ve lost my way—give me your hand to hold in the darkness’” (162).

When I read this part, outside in the Georgia heat, over six hundred miles away from my childhood home and my mother, I had to set the book down and breathe.

For all of the parts of this novel that have aged poorly, this doesn’t: this still resonates almost a decade later—the desperate hope that your mother will comfort you, guide you out of the dark hole that you’re in, that she’ll accept you and love you even when you fuck up and make shitty choices. I feel this urge when I’m at my lowest. When I’m at my lowest, when I’m separated by distance from friends and loved ones, I think, “I want my mom.”

I don’t call her.

Stephen wants her mother to love her and guide her at her lowest point. It’s a natural feeling when you’re a child to a parent, no matter how old you are.

As she, heartbreakingly, much like many lesbians before and after her have learned, being a mother does not mean she’s equipped to care for you, accept you, or love you as you need it.

Lady Anna looks at this child she birthed, who she can’t relate to, and does not even try to understand.

She sees an abomination and banishes Stephen from the home she loves.

Anna and Stephen are estranged for the rest of the book.

Their fall-out is written with such precise heartache that I can only imagine a young Radclyffe Hall’s face falling as she realizes her mother can never love her in the way she needs and writing that anger and betrayal into this novel.

This novel’s one-hundred year anniversary of publication will be in eight years. The Well of Loneliness is firmly in the 1920s in terms of its politics, language surrounding sexuality, gender identity and presentation, but the character of Stephen is one that leaps off of the page and finds resonance decades on, despite the tragic, harrowing end. Other readers beyond myself have found something in Stephen Gordon’s tragic story that’s relatable: as said by novelist Donna Allegra, “‘I, a black girl, Brooklyn-born and raised, had something important in common with this upper-class British noblewoman, something beyond a love of fencing and riding horses” (Green 281). This isn’t a book I would recommend to a young reader just beginning to question their sexuality, their gender identity or lesbianism. This is a book you read to have a better scope of and understanding of the history of lesbian fiction, trans fiction, queer literature as a whole, and how texts respond to and interact with one another.

At the time of the novel’s publication, Virginia Woolf’s equally gender fluid Orlando had released and she was one of the few authors to stick up for Radclyffe Hall during the censorship trial—despite finding the prose of the book itself middling, middlebrow and insipid. It was the principle of the matter for Virginia Woolf. Few of the literary elite of the time did the same, which she scathingly noted.

“Most of our friends are trying to evade the witness box; for reasons you may guess. But they generally put it down to the weak heart of a father, or a cousin who is about to have twins.”

Some things never change.

At the time of my finishing this essay, the Supreme Court of the United States has overturned Roe v. Wade: the landmark case that made abortion a constitutional right. Now overturned out of a desperate ploy and systematic attempt to make the Christofascist, white supremacist ambitions of the sitting government all the more obvious and plain to see. This will not banish abortion from the ether.

It will simply make it, once more, dangerous, unsafe to perform, and will murder millions of people.

In the past three years, there’s been hundreds of legislation pushed into local courts and districts to criminalize being trans, many of which have been passed. Teachers in Florida can lose their jobs if they even allude to the notion that being anything other than heterosexual and cisgender exists. Maus has been removed from school libraries for being ‘obscene’ although its a children's graphic novel to remind readers of the horrors of the past and to avert it. Clarence Thomas has made it clear that he wants to overturn Griswold (birth control), Lawrence (same sex intimacy), and Obergefell (same-sex marriage) next.

The Well of Loneliness is a manifesto-novel that serves as a plea to be seen as human: that’s what makes it so terrifying to those in power and those who wish to leech off of the powerful. They don’t want to see anyone who isn’t straight, white, or a cisgender man as human, because that’s not how they gain power and capital.

This novel does indeed fall into the Bury Your Gays trap by the end (although not for the main couple of Stephen and Mary, but another lesbian couple entirely: Stephen escapes the trappings of marriage and death by the end, no matter how odd the final two pages) but for all of its many, many issues (which I could write entire book chapters about), it’s still resonant now. It’s an important part of our history and I’d be loathe to have not read it.

I just advise that you read this not to understand your own sexuality or find validation in it, because the novel ends unhappily and can read as fatalistic, nihilist, based on its ending. Read it from a place of trying to understand its place in history and why it’s important, especially in the sphere of queer literature. You can read the novel as a lesbian story and you can also read it as a trans story. Both are prevalent within each other and it moves about this realm across genre and decades. We are still responding back to this novel, its legacy, its purpose as a cry for tolerance and a scathing condemnation of a heterosexist world in our work, wrangling with a world that is violently resistant to change.

“The Well of Loneliness offers a reminder that identities, whether of literary movements, of genres, or of persons, are narrative effects that are continually subject to rereading and rewriting” (Green 292).

This isn’t a book you read to see a happy ending, but for all of the things that haven’t aged well, there’s just as many parts of this book that do. It’s a firmly mixed bag, but one I’m glad to have read and one that shouldn’t be censored nor forgotten. I’d just tread this book with caution and be ready to look at it as a piece of history.

Whether you’re aware of it or not, you’re actively in conversation with the legacy this book has left behind.

Do not give into nihilism. It’s what they want.

Bibliography:

Green, Laura. “Hall of Mirrors: Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness and Modernist Fictions of Identity.” Twentieth-Century Literature. Vol. 49. Issue 3. Fall 2003. 277-297.

Hall, Radclyffe. The Well of Loneliness. Anchor Books. 1928.

Joyce, Kathryn. “How this tiny Christian college is driving the right’s nationwide war against public schools,” Salon. March 15 2022. https://www.salon.com/2022/03/15/how-this-tiny-christian-college-is-driving-the-rights-nationwide-against-public-schools/

Klein, Kathryn. “The Well of Inspiration: Radclyffe Hall and the Growth of Popular Lesbian Fiction in America” The Journal of Popular Culture. Vol. 52, No. 3. 2019.

Lloyd, Alice. “The College that Wants to Take Over Washington,” Politico Magazine. May 12 2018. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/05/12/hillsdale-college-trump-pence-218362/

Popova, Maria. “November 9, 1928: The Trial of Radclyffe Hall and Virginia Woolf’s Exquisite Case for the Freedom of Speech,” The Marginalian. November 9 2016. https://www.themarginalian.org/2016/11/09/well-of-loneliness-trial-of-radclyffe-hall-virginia-woolf/